Scientists woke up ancient microbes, and now they’re worried. But not for the reason you might think.

Sleeping in the Ice

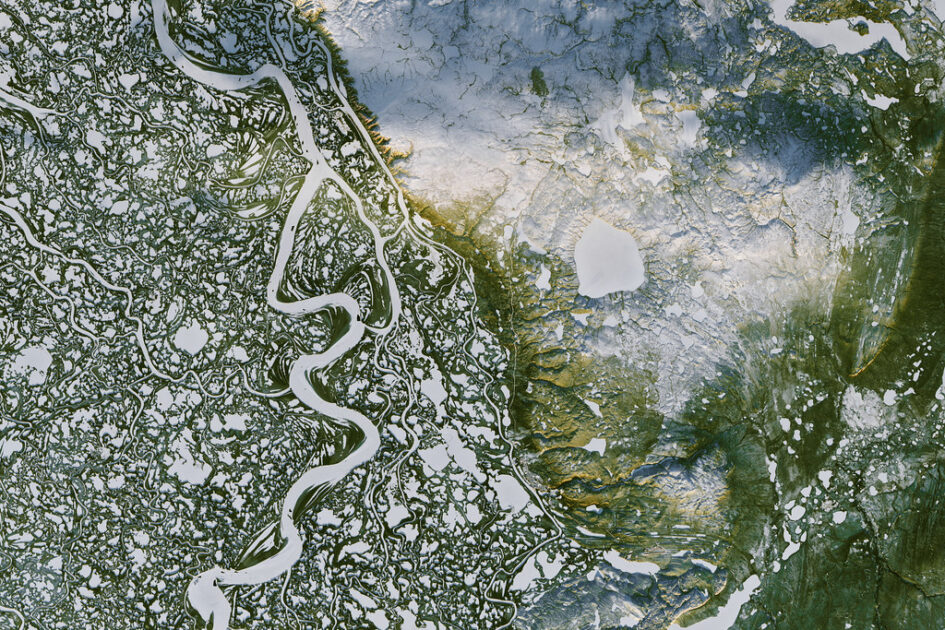

It’s not the first time scientists have “resurrected” ancient germs. All over the coldest parts of the world, microbes have been locked in permafrost—a frozen mash-up of ice, soil, and rock—for tens of thousands of years. When researchers dig up these icy samples and gently warm them, the microbes sometimes stir, stretch, and get back to work.

A few headline-grabbing examples:

- 46,000-year-old worms from Russian permafrost

- 30,000-year-old and 48,500-year-old viruses from Russian permafrost

- A 42,000-year-old bacterium from the Alaskan tundra

- An 8-million-year-old bacterial spore from Antarctic ice

Does this sound like the plot of a bad horror movie? Luckily, most germs aren’t actually dangerous. For example, they might infect amoeba (a one-celled creature), but not humans. But a horror-movie scenario isn’t impossible. A decade ago, anthrax from melting Russian permafrost killed a 12-year-old boy.

A quick clarification: these aren’t germs “coming back to life,” because they didn’t die in the first place. Instead, when temperatures got cold, they slowed down and took a nap. Some of the bacteria may have formed a protective shell known as a spore.

So What’s New This Time?

This time, scientists weren’t just looking to wake up the microbes. They wanted to observe how they lived—and how their growth might impact the ecosystem around them.

For that, they ventured into a cold, musty research tunnel in Alaska, carved decades ago straight into permafrost so ancient that mammoth bones still poke out of the walls. They collected chunks of this frozen ground and hauled them back to the lab.

Once safely back aboveground, they gently thawed the samples in sub-60 degree water—similar to the wet conditions that the melting permafrost might experience during a warm Alaskan summer.

Then, they waited.

At first, not much happened. The microbes slowly began to wake up. They occasionally divided, forming new creatures. This sluggish activity continued for several weeks.

But by 6 months, the microbes began to flourish. It digested the carbon-rich remains of ancient plants and animals frozen into the permafrost, “breathing” out growing amounts of carbon dioxide and methane.

And that was a problem.

Melting Permafrost

All around the world, permafrost is melting. This is part of the global rise in temperatures caused by climate change.

Melting permafrost will make it harder for wildlife to survive on the tundra, contaminate local water supplies, and cause the muddy ground to sink. But it could also trigger a vicious cycle.

More CO₂ warms the planet. More warmth melts more permafrost. More permafrost melt releases more carbon. You see where this goes.

These emissions are more than microbial morning breath. It’s estimated that the Arctic permafrost contains double the amount of carbon currently in the atmosphere. Scientists are still trying to understand just how much damage this could cause.

The Microbial Story

Climate change will affect all of life on earth, down to the smallest microbes. But it’s more complex than that, and we can’t forget it. Life on earth won’t just die: it will change. Some of these changes might be dangerous, further fueling the greatest challenge humanity has faced yet.

These microbes, buried for millennia, have a message for us. We can’t afford to let the permafrost melt. The time to take climate action is now.

Source: Strain, D. (2025, October 2). Researchers wake up microbes trapped in permafrost for thousands of years. University of Colorado Boulder. https://www.colorado.edu/today/2025/10/02/researchers-wake-microbes-trapped-permafrost-thousands-years

Read more: Pathogens in the Permafrost

Leave a Reply