If the name “screwworm” makes you squirm, good—you’re getting the right idea. It’s a type of blowfly whose larvae burrow into living flesh.

Yeah. Ouch.

What Is a Screwworm?

The New World screwworm is actually a type of fly. It looks like a regular black fly, except it’s bluish gray.

Source: Animal and Plant Inspection Service. (2025). New World Screwworm. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cattle/ticks/screwworm

But it’s not the adult fly you need to worry about: it’s the baby.

Screwworms lay their eggs in living animals, typically in cuts, scrapes, and other open wounds. When the eggs hatch, the maggots (also known as larvae) sink their mouth hooks into the animal’s flesh and dig in a screw-like motion. As they crawl deeper and more painfully into the flesh, the wound becomes bigger, begins to smell, and attracts even more flies. Eventually, maggots burst from the wound and fall to the ground, where they finish growing.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About New World Screwworm Myiasis. https://www.cdc.gov/myiasis/about-new-world-screwworm-myiasis/index.html

It’s no wonder that scientists call the screwworm “Cochliomyia hominivorax,” which is literally Latin for “man-eating fly.”

The good news is that human cases are rare. This parasite is far more common among cattle and other livestock.

Where Does It Come From?

As the name suggests, the New World screwworm is native to the Americas. Today it’s mostly found in South America and the Caribbean. But until the 20th century, it also infested the southern United States, thriving in warm states like Texas and Florida.

The Elimination of Screwworm in the United States

From the 1920s to the 1950s, screwworm killed hundreds of thousands of livestock in the United States. Newborn calves were especially vulnerable: their healing belly buttons were basically “open for business” signs to female screwworm flies.

In the 1950s, U.S. scientists came up with an idea: use radiation to sterilize male screwworm flies, then release them into the wild. Female screwworms are loyal—they only mate once. So if their one-and-only partner was sterile, that was the end of the line. No more screwworms.

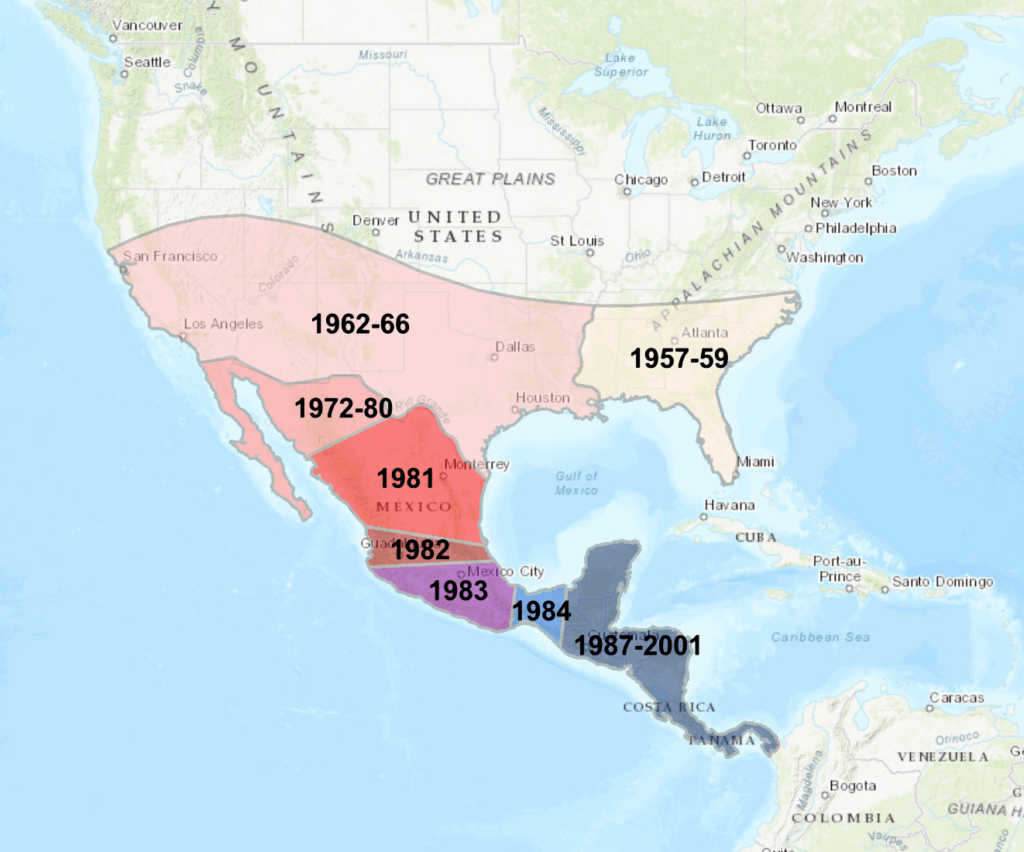

The idea worked: by the early 1980s, screwworms were eliminated from the United States. But the work didn’t stop there. The United States and its partners have continued releasing the sterile flies further southward, into Central America, creating a protective “barrier zone” to keep the screwworms from flying back north. Talk about putting the screw to screwworm.

Source: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. (n.d). New World Screwworm Story Map. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cattle/new-world-screwworm-mapping

The Return of the Screwworm

Fast forward 80 years: Panama saw a spike in screwworm, jumping from an average 25 animal cases a year to over 6,500 animal cases in 2023. From there, the fly spread rapidly through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, Belize, and El Salvador.

Cases haven’t just surged in animals (although most cases remain in livestock). Mexico alone has seen 41 people infected with the parasite so far this year. Nicaragua has had over 120 cases in people.

Now, the outbreak is beginning to touch the United States. This week, a man from Maryland got infected with screwworm after visiting El Salvador. Now recovered, there’s no sign that he spread the disease to any animals or people.

Why Is This Happening?

So why is this parasite suddenly spreading again after decades of control? It’s not clear. It could be that the latest batch of sterilized male flies wasn’t as effective as it should have been, allowing the population to grow. Or infested cattle may have moved across borders, possibly through illegal cattle trafficking. These smuggling networks transport stressed, injured animals: the perfect breeding ground for screwworms. Climate change could also play a role, with warming temperatures creating good conditions for the flies to breed.

The Global Health Response to Screwworm

But just because screwworm is tenacious doesn’t mean it’s invincible. The United States and other countries have taken several steps to combat the spread of this nasty bug:

- Trade restrictions: The U.S. has stopped live cattle imports from Mexico multiple times and enforced inspection protocols.

- Sterile-fly facilities: The United States is revamping an existing sterile-fly production facility in Mexico and preparing to open a new one in Texas.

- Regional collaboration: Countries across Central America are amplifying surveillance, training, outreach, and animal movement controls.

Together, these strategies can help keep screwworm in check.

Why Screwworms Still Matter

Screwworm might sound like a bizarre American history lesson, but in much of the tropics, it’s still a pressing threat. For farmers in low-resource settings, a single infected cow can mean losing food, income, and stability for an entire family.

Outbreaks don’t just kill animals; they disrupt food security, devastate rural economies, and threaten human health. That’s why countries continue to invest in eradication. These efforts aren’t cheap, but they sure beat the staggering economic costs of a large-scale outbreak in the U.S. agricultural system, not to mention the animal and human suffering involved.

We beat screwworm once with science and international cooperation. The real question is: can we keep it from screwing with us again?

Learn more: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cattle/new-world-screwworm-mapping

1 Pingback