Two facts about me:

- I was born with a heart defect.

- I’m a lifelong reader.

At first, these two facts might seem unrelated. To understand the connection, you have to go back to a quiet spring evening over twenty years ago, to a toddler snuggled in her mother’s lap, pointing to the smiling characters of a picture book. It wasn’t the first book that she read to me, but it’s the first one that I remember.

The book was Grover Goes to the Hospital.

Like Grover, I was also getting ready to go to the hospital. My mom was trying to prepare me, as best she could, for open-heart surgery.

Grover helped me to understand what was going to happen in the hospital. His story helped alleviate my fears of the many mysterious machines, endless hospital hallways, and other unknowns. There were even some parts I was excited for—namely, the hospital playroom, which would be filled not just with shiny new toys, but also other kids like me.

As I grew up, I didn’t think much about the scar on my chest that marked me as different from my playmates. But when I reached middle school, like many other preteens, I started to pay more attention to my body. For the first time, I started questioning whether my heart was different than theirs, if those differences meant that I was somehow broken. I began to wonder about other kids who had survived—and even thrived—after major illnesses. So of course, I turned to my trustworthy companion: the library.

I scoured the shelves for chapter books about teens with medical conditions. But I couldn’t find many. Most of the ones I did were about depressed kids with terminal cancer. Books like The Fault in Our Stars, which was at the height of its popularity, left me feeling hopeless and alone.

Since then, I’ve remained fascinated by the healing powers of stories—and the misunderstandings and hurt that occur in their absence. So when I had the opportunity to practice qualitative research methods in a grad school “mini study,” I thought back to the books I hadn’t been able to find in middle school. I decided that for my project, I would interview middle-school librarians about what they thought of the current portrayal of disabilities. The question launched me into the rapidly growing world of disability representation.

The Importance of Disability Representation

These days, parents and teachers are on the lookout for kids with disabilities and different ways to help them thrive. In 2021–22, up to 15% of students at US public schools received special services. Yet disabled characters remain one of the most underrepresented groups in children’s literature. As a result, many classroom libraries don’t feature disabled characters.

This absence is a major missed opportunity to promote inclusion. The stories and characters you meet as a child have a lifelong effect on the attitudes you develop toward others. Books often serve as ‘windows and mirrors’ that can help readers walk in someone else’s shoes or see that they are not alone. More and more people are realizing the importance of diverse characters in fostering acceptance and belonging in communities. Some research even suggests that reading books about disabled characters can improve interactions between disabled and nondisabled students.

But it’s not enough to simply include disabled characters: they need to be multi-dimensional and relatable. Otherwise, underdeveloped characters could actually reinforce stereotypes and misconceptions about disabilities. Although many researchers have studied the portrayal of characters of different races, ethnicities, and sexual orientations, few have investigated the portrayal of disabled characters. The little research there is, tends to focus on picture books.

Disability in Picture Books

In books for younger readers, disabled characters are rare. When they do appear, they are often pigeonholed into the roles of outsiders, savants, or sidekicks. Miracle cures and inspiration porn, (a patronizing focus on ‘overcoming’ a disability) are also common in these books.

However, these trends are changing. During the last twenty years, disability has appeared more frequently in children’s literature. Nonetheless, many modern books continue to represent disabled characters in well-intentioned but potentially harmful ways. Often, picture books about disability emphasize the similarities between disabled and able-bodied characters. By focusing on the ‘normal’ parts of disabled lives, these books teach children that disabled peers are not so different after all. For example, one common storyline features an able-bodied main character describing a friend, and all the ‘normal’ activities they do together, before revealing that the friend has a disability.

These books are meant to promote inclusivity and acceptance. However, the renewed emphasis on normality might actually reinforce the us-vs.-them binary. In general, these books are written for an able-bodied audience and use patronizing language and concepts. Instead, many activists call for books celebrating the quirks and diversity of disabled bodies.

The Project

Even less research exists about books written for kids ages 8–12, although it is clear that an increasing number of these books feature disabled characters. Some signs indicate that portrayals of disability have changed: for example, one 2003 book focused on how an autistic character could not solve a mystery because of his disability, whereas newer books show how autism can help characters solve mysteries. But there’s still a lot of unanswered questions about how these books describe disabilities.

To learn more, I asked five middle school librarians about how they think disabilities are portrayed in books for that age group. I found one participant through volunteer work I had done with a local school in Atlanta and four through their active presence on “Bookstagram” (coincidentally, those four librarians all happened to be from Texas). All five interviewees identified as female and had worked as middle school media specialists within the last two years. They each had 4–13 years of experience.

There are many ways to define disability, each of which has benefits and drawbacks. For this project, I considered disability to be a physical, emotional, or mental condition that impairs functioning in an able-bodied society. Likewise, I considered middle-grade literature to be any text-based storytelling method primarily aimed at kids aged 8–12 years old. During the interviews, I asked about a wide variety of themes, including the frequency of books about disability, portrayals of disabled characters, and student interest in these books. The interviews were conducted over Zoom in Spring 2022.

How Common Are Disabled Characters, Anyway?

All five librarians agreed that there is a lack of disability representation in books for middle school students. Morgan, who had worked as a librarian for 13 years, said “From all my years of being a media specialist, I do not recall a lot of books where the characters have been disabled: where they’ve been either deaf, blind, or in a wheelchair. A few, but not a whole lot, I’m going to be honest.” Similarly, MS said that before she started to actively diversify her collection, she could list the books that portrayed disability “on one hand.”

However, all the librarians also noted that disabled characters were becoming more common. Some attributed the increase in diversity to a push by the publishing industry, whereas others pointed to an increase in disability advocacy.

Nonetheless, they disagreed on exactly how common disabled characters are. When I asked them to estimate the current proportion of middle-grade books with disabled characters, they gave a wide variety of answers ranging from 3–5% to 25%.

To demonstrate the lack of representation, Morgan pulled up Follett Title Wave, a book database and purchasing tool for school librarians. She performed a search for “fiction book with children with disabilities,” which returned 57 nonfiction books and zero fiction books. In contrast, Luisa used the same tool to search “physical disabilities and special needs” and found 236 results, 79 of which were fiction (however, Luisa currently works at a high school, so her account and filtering settings would have revealed books categorized for a high school, rather than middle school, audience).

Different types of disability

The librarians reported that some disabilities were more likely to be portrayed than others. For example, they all noted an increase in the number of books that featured characters with anxiety or depression. Leah explained, “That’s one of the most popular things right now: depression, anxiety, dealing with that.” Some attributed this trend to the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced many schools to turn to virtual learning. This shift, the librarians explained, contributed to a rise in mental health issues. As a result, many recently published books discuss mental health, an issue that is of increasing importance to their audience.

However, the librarians disagreed about the prevalence of physical disability in literature. Some said that physical disability was rarely portrayed. For example, MS said: “I still see a lack of physical disability. Every once in a while, I’ll see a book with a child that’s in a wheelchair or uses crutches, or has a missing limb or something like that. And so I feel like as far as the physical disability, we still have a long way to go to make sure that every single child that is struggling with something like that is represented.”

On the other hand, Morgan said that the only disabled characters she’s seen were deaf, blind, or used a wheelchair. During the interviews, librarians referenced several titles, nearly all of which featured a protagonist with a physical disability (usually a birth defect, deafness, or cerebral palsy). Luisa pointed out that even though autism is much more common than deafness, she’s seen more examples of deaf characters than autistic characters. “Don’t get me wrong, we need books about deaf students. We need that, but we also need books about people who are struggling with autism,” she said. Other librarians also noticed a lack of books about characters with developmental disabilities such as autism or Down syndrome.

What Does a Disabled Character “Look Like?”

Most of the librarians believed that disabled characters tend to be portrayed in a positive way. For example, modern books often show disabled characters as real, complex people that readers can relate to. Leah said that these books show that people with disabilities can still lead so-called ‘normal’ lives. However, she wondered whether disabled people might disagree, asking “Do they feel like they’re being portrayed negatively?”

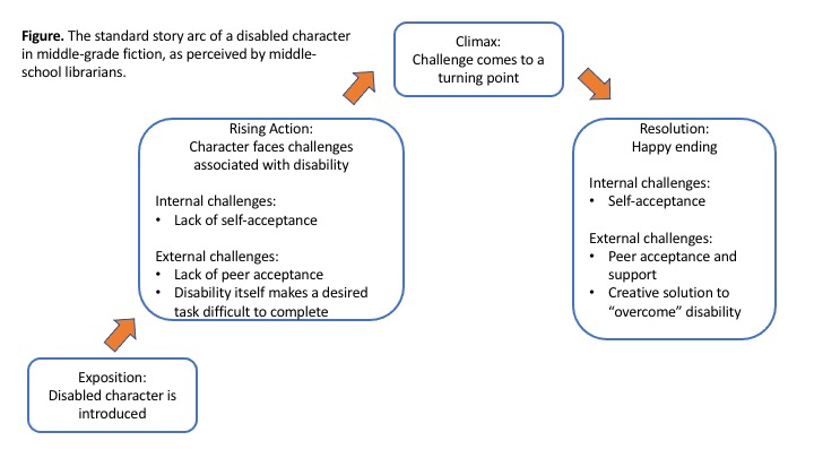

Still, disabilities are often portrayed as a burden. Luisa said the books are “always about the struggle instead of the accomplishments.” For example, many (though not all) books revolve around a character’s disability as a plot point. When asked about how disabilities affect a book’s plot, MS explained:

“I think it depends on the story. I would hope that if it’s an adventure, the character just happens to be in a wheelchair and it’s not distracting or anything like that at all. And so I don’t feel like it should distract from the story. I feel like if that’s what it’s about, just a kid that happens to be in a wheelchair, that is off on adventures, then that’s what it should be.

But if it’s a story that’s actually teaching them about a particular illness, or a topic like that, then I feel like it should add to the plot and it should be described well and it should be showing all the different ways that that child struggles with it or overcomes having that disability. So I feel like it just depends on what the book is trying to achieve.”

MS

Luisa said that the disability is “usually a pretty central part of the plot.” For example, the disability might cause a character to struggle with completing a task or fitting in with nondisabled peers. Generally, characters are able to find a creative solution to their problem or teach their peers a lesson about inclusion. Luisa explained, “The ending of the book always talks about how the disabled characters were able to show people [that they were capable and deserving of respect]…and get acceptance and learn and grow and maneuver their day-to-day lives.”

Katelyn added:

“Yeah, a lot of the times the disabled characters are shown at the beginning as being really sad or frustrated. And then towards the end of the novel, something happens to them and they’re able to cope. And so at the end they do…not ‘get over it,’ but…they’re able to move on.”

To illustrate this idea, Luisa pointed to the book Wonder, whose conclusion shows a bully apologizing for his actions. She is skeptical of this optimism as well as the focus on overcoming disabilities, explaining, “The characters always find a solution. And disabled people’s lives are not always about finding a solution.” However, she admits that the nature of a children’s book requires a sense of resolution. “You always have to end the book,” she says.

The difference between middle-grade and young adult books

Some participants noted that books for middle-grade readers represented disability in a more positive light than books for teens or young adults. MS said, “I feel like with the more middle-grade titles, you’re going to have a little bit more of a happy ending. Struggled for a little bit, but then you know, ‘I got all better’ and everything like that.” Middle-grade books tend to culminate in a celebration of acceptance or the solving of a challenge, but young adult books “just show that life doesn’t always end with butterflies and everybody understanding and accepting of you,” said Luisa, who now works at a high school.

But the librarians didn’t think the differences in portrayals was a bad thing. Instead, they felt it more appropriately reflected the emotional maturity of readers who might be too young to comprehend or be able to cope with some of the larger challenges associated with disability. Instead, Luisa emphasized the importance of giving middle-school students hope about overcoming challenges.

All the librarians noted that overcoming challenges was a common moral in books about disabled characters. Another common moral was to not judge people because of their disabilities. For example, Luisa explained that the entire goal of the main character in Out of My Mind was to convince others that she was highly intelligent despite having cerebral palsy. The librarians considered these themes to be important lessons for both disabled and able-bodied students.

Do Students Want to Read About Disabled Characters?

The librarians disagreed on student demand for books about disabilities. Some said that most students didn’t want to read these books. For example, Morgan said that many students dislike reading about disabled characters because of “the guilt factor.” She explained that even if a character is portrayed positively, students feel bad for that character. Rather than dealing with those emotions, students will gravitate towards more light-hearted fiction books.

However, some librarians disagreed. For example, a few discussed how students might seek out nonfiction books to learn more about themselves or others. Luisa had one student who checked out five nonfiction books about anxiety before sharing, ‘I want to learn more before I talk to my mom about how I’m feeling.’” Other students were eager for the emotional connection to a character who had experienced similar struggles. Leah felt that books with disabled characters are “popular” because students are looking for stories they can relate to.

Katelyn, who has dyslexia, explained how powerful her experience of reading about a dyslexic character was. She imagines students would be just as touched. “They would feel that they belong,” she said, “and they don’t feel like an outcast.”

Lessons Learned

In the past, disability was rare in children’s literature. When it did appear, it was often portrayed as a bad thing.

Now, things have changed. There are more middle-grade books than ever about characters with disabilities. Titles like Roll With It, El Deafo, and Wonderstruck have given powerful, fun, and unique voices to characters whose stories have never been told before. More are being published every year, part of the rising tide of #DiverseBooks and #OwnVoices. I worked on this project in 2022, and since then, even more wonderful books have featured characters with mental health issues, autism, POTS, and more.

However, the struggle for representation isn’t over yet. There are many childhood health conditions that still haven’t been written about or are often portrayed according to stereotypes. And sometimes, well-written books about disabled characters still struggle to find their way to library shelves.

Long story short:

- We need more kids’ books about every type of disability.

- Disabled characters need to be portrayed as authentic people, not stereotypes.

- Kids should have access to books about characters they can identify with.

How to help

As a reader and writer, I’ll be on the active lookout for authentic books about characters with disabilities, especially books written by disabled authors themselves. Here are some ways you can help:

- If you can, buy books about disabled characters. The power of the purse means a lot to authors, publishers, and the entire industry.

- Follow disabled creators on social media. You can find them using hashtags like #OwnVoices. A ‘like’ or ‘comment’ is a cost-free way to show your support. Share their posts and amplify their work!

- Request that your library stock books about disabled characters. Some libraries can justify buying a book based on a single request, whereas others might need multiple people to request the same book (keep in mind that this varies from library to library, and other factors—mainly budget—also play a role in book orders). Name a specific book so that librarians can keep track of requests.

- If you read a book that gives into stereotypes about disability, let the author know how you feel. Many times, they’re open to learning about this issue and will be more mindful in their future books.

- Share your own disability story! Write about it, draw about it, sing about it, whatever feels most right to you.

Book recommendations

I’ve read several great books about disabled characters. Here are just a few of my favorites:

- Breathe and Count Back from Ten by Natalia Sylvester (hip dysplasia)

- Wonder by R.J. Palacio (facial difference)

- El Deafo by Cece Bell (deafness)

- Wonderstruck by Brian Selznick (deafness)

- Daisy Woodworm Changes the World by Melissa Hart (Down syndrome, autism coding)

- Wink by Rob Harrell (cancer)

P.S. Learn more about my book Chrysalis, which features heart defect and developmental disability representation.

Supplemental info

This mini-study was completed for a class project and therefore did not require IRB approval. Some quotes have been lightly edited for clarity. Participants gave informed consent to engage in the project and to be featured (using pseudonyms) in a blog post about the findings. You can read more about the methods below. If you’d like to learn more, send me an email at daltomara(at)gmail.com.

Research Question

Research Question: What are the perceptions of school librarians on the portrayal of disability in middle-grade literature?

Sub-question: How do middle-grade students engage with books about disabled characters?

Research Statement

The purpose of this qualitative study is to describe the portrayal of disability in middle-grade literature as perceived by middle-school librarians. At this stage in the research, disability will be generally defined as a physical, emotional, or mental condition that impairs functioning in an able-bodied society, and middle-grade literature will be defined as any text-based storytelling medium serving an audience of kids aged 8-12 years old.

Methods

This mini-study relied on qualitative research methods for their ability to explore participants’ perceptions and thought processes (Hennink et al., 2020). In-depth interviews enabled me to explore the ways librarians think about disability and diversity, and not just the quantitative data on how many books on disability exist. For example, knowing the exact number of books about disability exist would not shed light on whether librarians are aware of these books, if and how they share them with their students, and why they might like or dislike those portrayals of disability. This information is crucial to understanding how media specialists and students interact with these books.

For this project, five interviews were conducted with current and recent (within two years) media specialists employed at middle schools. All participants were female and had been media specialists for 4–13 years. Four participants work at public schools in Texas and one works at a charter school in Atlanta. The four participants from Texas all have an active social media presence on Instagram, where they posted about middle-grade books. Pseudonyms were used to protect participant anonymity.

Sampling and Recruitment

My initial method of recruitment was through a gatekeeper I knew from my previous literacy work with the Atlanta Public Schools. I have known this gatekeeper for several years and we have a trusting relationship, and I hoped that she might be able to introduce me to media specialists in the community. However, this gatekeeper referred only one participant to my study. I attempted to use snowball sampling by asking that participant to refer colleagues to my mini-study, but this technique was not successful. As a result, I switched my main method of recruitment to social media, specifically by posting on Facebook and Instagram. Although I didn’t find any participants through Facebook, I did find several through Instagram. These participants all ran accounts related to their work as a middle-school media specialist. These participants were eager to talk and share their experiences, however, it is important to recognize that their perspectives might differ from middle-school librarians as a whole. For example, social media is commonly used to promote diverse books, so librarians with Instagram accounts might already be more aware of the portrayal of students with diverse backgrounds, including disability, in their collections.

Data Collection Methods

Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted during March–April 2022 over Zoom because of logistical constraints. The participants all sat at their desk in the school library during school hours. This method enabled me to collect rich data about participants’ personal experiences and opinions, which they might have been more reluctant to share about in a focus group (Hennink et al., 2020). For example, some participants shared their own experiences with disability and its associated stigmas. Others shared opinions that they felt would differ from their colleagues. Zoom was a helpful tool in that it enabled me to interview participants living in other states; however, I ideally would have liked to interview participants in their libraries, where I could have observed how the physical layout or decorations might have promoted or discouraged inclusivity among students looking for books.

Interview Guide

I carried out semi-structured interviews with the aid of an interview guide (Appendix I) that I designed. This guide helped me to maintain a specific focus on certain unifying themes throughout the interviews, and to transition smoothly between those themes. The interviews opened with introductory questions that helped me to understand the context of the participants’ answers, for example, how they defined disability and whether they or a loved one had experienced a disability. The interview questions then shifted to the themes of “Disability in Literature,” which asked about participants’ perceptions on the portrayals of disabled characters and “Disabilities in Schools,” which asked about student interest in books featuring disabled characters. I closed the interview by asking about participants’ hopes for future books about disabled characters and whether they had anything else they wanted to share. Throughout the interviews, I used the silence and “Tell me more” probes to elicit further responses. I also probed about how answers might vary in regard to representation of different types of disabilities.

The interview guide remained relatively stable throughout the interview process; however, I added questions such as “How would you describe your school?” which I realized were necessary for context.

Logistics

All interviews were carried out on Zoom during school hours because of constraints with scheduling and distance. Participants sat in their desks in the school library, whereas I sat in my desk at home or at Rollins. Interviews lasted 40–60 minutes and were recorded and transcribed in verbatim.

Analytic Method

I coded and analyzed interview transcripts using modified grounded theory and textual analysis. I created a codebook (Appendix II) with several deductive codes that my previous literature review had suggested would be of importance. These codes included different types of disabilities and book genres, as representation seemed to vary across these categories. Throughout the coding process, I added, modified, and merged certain codes as I gained appreciation for their common themes and differences. I also added inclusion and exclusion criteria for each code. In addition, I realized the reoccurrence of several unexpected topics such as social-emotional learning and the COVID-19 pandemic. I added these terms to my codebook as inductive codes. Coding was completed using MAXQDA 2020, which allowed me to view and sort interview quotes based on their codes. I also compared my coding with a classmate who reviewed one of my interview transcripts.

Ethics

This mini-study was completed for a class project and therefore did not require IRB approval. However, I followed typical IRB protocol throughout the research process. For example, I collected informed consent by reading participants a detailed introduction to my project, its purposes, and its methods; answering all questions; and gathering verbal consent to participate and be recorded. All interviews were confidential and anonymized. I completed CITI training prior to beginning interviews, stored all files on a secure personal computer, and destroyed audio files after use.

Strengths and Limitations

My project, like many qualitative studies, drew its greatest strength from the robust, granular data yielded by in-depth interviews (Hennink et al, 2020). Individual interviews allowed me to explore themes in greater detail with participants depending on their comfort and experience, and also to probe more closely into the thought processes underlying their opinions. Therefore, my results provide a preliminary picture of how middle-school librarians think about disability representation in their collections, why they hold those perceptions, and their reasoning of how and why students interact with books about disabled characters. These are complex, multilevel themes that could not be captured in studies based in quantitative analysis, observation, or focus groups.

The greatest limitation of my project was that as a single, unfunded graduate student, I did not have the time or resources to give this project the thorough investigation it deserved. Under ideal conditions, I would have had the time and resources to interview participants until I reached saturation, to more thoroughly compare my code with colleagues, and to spend more time analyzing the results. For example, my small sample size made it difficult to find patterns between conflicting opinions. Because I did not reach saturation, I was unable to form a comprehensive model informed by a variety of attitudes. Finally, my interviews yielded a large quantity of data that I was unable to fully synthesize in a single project.

Future Directions

This mini-study yielded some rich data while introducing many new questions. To start, this mini-study did not reach saturation. Future studies should interview more participants to identify further issues in the topic area. In particular, investigators might like to interview male librarians, older librarians, rural librarians, librarians not from Texas, and librarians not active on Instagram, as these individuals were underrepresented in the study sample. It is important to note that this demographic make-up does not make my study results any less valid (the goal of qualitative research is not necessarily to sample a large number or variety of participants) but simply points to opportunities for further exploration (Hennink et al, 2020). It is possible that librarians from the described backgrounds might have very different feelings towards or perceptions of disability representation than those interviewed.

Future investigations might also interview middle-school students. In this mini-study, librarians described their students and how they believe the students think about characters with disabilities. However, student opinions might not align with what librarians perceive or expect. As the main audience to experience middle-grade books about disabled characters, it is important to hear their opinions directly. However, this process will require IRB approval.

Finally, future investigations might like to include a quantitative analysis of the books listed in Follett Title Wave or other databases frequently used by middle-school librarians. This analysis would provide data about how many books are currently categorized as being related to disability and their genres. However, qualitative interviewing of librarians would have to supplement this analysis, largely because the participants of this study indicated that these systems frequently miscategorize their titles.

Appendix I: Interview Guide

Introduction:

Hi, my name is Deanna, and I’m a graduate student at the Rollins School of Public Health. I’m currently taking a class on qualitative research methods and am conducting a mini-study about portrayals of disability in middle-grade literature.

This semi-structured interview should take about 45 minutes, and will be recorded with your permission. It will consist of open-ended questions so you can share your experiences and perspectives on the topic. I’ll be asking about things like diversity in library books, the ways disabled characters are described, and how students interact with books about disabled characters. There is minimal risk in participating in this study; however, we may discuss some sensitive issues, especially relating to disability and health. You don’t have to share anything you don’t feel comfortable sharing. Your participation is voluntary and we can take a break at any time. There are no incentives for participating in this project, although the findings could provide important insights into the topic.

Interviews are confidential and your data will be de-identified, which means that a pseudonym will be used and that identifying details will be changed or retracted. The de-identified data will be reviewed by my professor and classmates.

With your permission, I would also like to describe my findings in a blog post or magazine article. Unless otherwise directed, I’ll use a pseudonym and retract any identifying details.

I’ll delete the recording of the interview at the end of the semester.

Do you have any questions before we begin?

Do I have your consent to participate in this class project?

Do I have your consent to share these findings in a blog post or article?

Do I have your consent to record?

Thank you.

Opening Questions:

- Tell me a little about yourself. (age, background, etc)

- How long have you been a media specialist?

- How long have you worked with middle schoolers?

- How would you describe your school?

- How would you define disability? (Social/emotional conditions like anxiety? Invisible diseases like diabetes?)

- If you feel comfortable sharing, how has disability (whether your own or that of someone close to you) impacted your own life?

Disability in Literature:

- What is the current dialogue surrounding diversity in literature? (racial, ethnicity, sexuality)

- What is the role of disability in this dialogue?

- How do you think disability should be portrayed in middle-grade books?

- How common are disabled characters?

- What kinds of disabilities do these characters have? (developmental, physical)

- How are specific disabilities and diagnoses named or labeled?

- How are disabled characters described? (Sad, angry, pitiful, inspirational)

- How does a character’s disability affect the plot of a book?

- How does a character’s disability affect the mood of a book?

- If applicable, how does a character’s disability affect the moral of a book?

- How are disabled protagonists described differently than disabled supporting characters?

- What is positive about these portrayals?

- What is negative about these portrayals?

- How do these portrayals reflect stereotypes (or not)?

- Do these portrayals vary for different types of disabilities?

- How have these portrayals changed over time?

Disability in Schools:

- What kinds of disability do you see most frequently in the school setting?

- Does literature generally reflect the disabilities that are most common among students?

- How often is disability discussed in schools?

- How do students talk about disabled characters?

- In class discussions?

- In the hallways?

- Discussions with you?

- What are some barriers to obtaining books about disabled characters?

- How popular are books with disabled characters?

- What influences the popularity of these books?

- How does interest vary among students?

- I’ve heard that books can act as mirrors and windows.

- How do children with disabilities see themselves reflected in literature?

- What value do these books have for children without disabilities?

Closing Questions:

- Going forward, what do you want to see in future books featuring children with disabilities?

- What is your advice for librarians seeking to diversify their books?

- Is there anything else you think I should know?

Closing:

Thank you for your time. Your insights are really important for this project, and I appreciate your willingness to share.

Would you like me to send you my project when it is finished?

In my report, what would you like your pseudonym to be?

Thank you again, and have a good day.

Appendix II: Codebook

| Code Number | Code | Subcode(s) | Definition | Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Example |

| 1 | Disability definition | Participant’s personal definition of disability | Includes: definitions that consider the fact that there are many different types of disabilities Excludes: types of disabilities considered outside the context of a participant’s definition of disability (use 5) | “I would define disability as, uhm, someone that…I hate to use the word…like othered or not normal, because that’s just not true. I feel like so many people with disabilities are just as capable and just as able, and so it’s kind of like with neurodiversity, it’s something that falls under a diverse category of…and it could be physical, mental. You know, lots of different disabilities out there, but I feel like it’s somebody that is struggling with something physical or mental.” | |

| 2 | Diversity | Representative of a wide range of different lived experiences. May pertain to disability, race, ethnicity, gender identity, or sexual orientation. | Includes: intersectionality, diverse representation in books, diverse representation among students | “I know. So for the past, I’d say you know, five to seven years, every conference I’ve gone to, every training, whether it was local, state or national, has focused on diversity and inclusivity. And it’s interesting because I feel like that is finally starting to spread out into the masses, right? And it’s become polarized and politicized as far as some people not truly understanding what we mean when we talk about creating a diverse and inclusive set of literature for our students, and so I feel like that the backlash that’s happening right now is kind of in response to the things that have been building in the education and library community over the last few years to make sure that every student that walks through our doors is seen and is reflected in a book in our library. Hopefully more than one. I started a diversity audit two and a half years ago for my collection, to make sure that we were where we needed to be. But we were not, and so I was not surprised about that finding at all. But it helps me now with my ordering and my purchasing. I’m very much more aware. My library is genre-fied 100%, so I can go and say, okay in my adventure section it was 79% white male. And that’s something that I need to work on. In addition to that, it’s also something the publishing industry is working on, is building towards. So you know, I feel like we were making a lot of great strides, but lately with all the book banning and challenging and censorship we are kind of in some ways at a halt a little bit. I personally am not, because I refuse to, you know, let some small group of people, you know, halt a lot of progress that I feel I have been making in my library. I won a grant last year through our ______ to purchase diverse and inclusive titles. I’m also the ______ for my campus and my district, so I still continue to run _____ and continue to purchase diverse literature. It’s just the conversation lately has changed to us defending that instead of putting our focus on growing our collections in that way sometimes.” | |

| 2.1 | Inclusion | Efforts to make a space, school, or book collection more diverse, welcoming, and accepting | Includes: inclusive infrastructure, welcoming and accepting attitudes, how to diversify library collections Excludes: non-inclusion, lack of inclusion | “Diversity in literature, most of the common thread is talking about inclusion, more so than you know labeling someone as disabled or someone being, you know, considered having a disability. So more of the talk is about inclusion and how we can make everyone feel comfortable despite, you know, what may be going on physically with their bodies, mentally, but it’s all about inclusion.” | |

| 3 | Labels | Descriptions, especially judgmental, of a marginalized group of people | Includes: stereotypes, slurs Excludes: Categories/tags (use 4) | “But I just feel like disabilities is not a good word. I think people are just different.” | |

| 4 | Categories/Tags | Books or displays that are specially marked to indicate the presence of a disabled character | Includes: lists or categories created by librarians, hashtags or keywords on booksellers’ websites Excludes: labels (use 3) | “In our checkout system, I have a specific category for, like, disabled, you know, mental health, mental trauma, all that. I have, like, a category and kids can go and look through that and that’s how they check out books.” | |

| 5 | Types of disability | Reference to the fact that multiple types of disability exist | Includes: the diverse nature of disability, specific types of disability, list of disabilities | “There’s different kinds of disabilities.” | |

| 5.1 | Developmental | Any disability that affects a person’s intellectual or behavioral growth | Includes: mental disabilities, Down syndrome, autism | “Down syndrome. Or, you know, another disability like that?” | |

| 5.2 | Physical | Any disability that affects a person’s movement, appearance, or sensory perception | Includes: deaf, blind, wheelchair | “People think of, most of the time, someone that is in a wheelchair, or possibly has something like, you know, a short arm or limb or something.” | |

| 5.3 | Emotional | Any disability that affects a person’s emotional state | Includes: depression, anxiety | “I see a lot more anxiety. Way more anxiety than I have in the past.” | |

| 5.4 | Invisible | Any disability that cannot be easily perceived by an outside observer | Includes: chronic illness, cancer, diabetes Excludes: developmental disability, emotional disability, learning disability | “My husband is a diabetic, and he would not want to be considered disabled. But, because of his diabetes, it can limit his activities and things that he can do.” | |

| 5.5 | Learning | Any disability that directly affects academic performance | Includes: dyslexia Excludes: developmental disability | “Uhm, like learning disabilities. I’ve read a lot of them that are talking about like topics like dyslexia.” | |

| 6 | Attitudes towards disability | Direct or indirect statements of how a participant feels about a disability | Includes: ideas about how disability “should” be portrayed | “Anxiety, I have a child that experiences that as well. I can understand that, so I have a lot of compassion when it relates to anxiety.” | |

| 7 | Genre | Classification of literature based on factual accuracy, narrative elements, images, and other textual elements | Excludes: Categories/tags | “My library is genre-fied 100%, so I can go and say, okay in my adventure section it was 79% white male.” | |

| 7.1 | Fiction | Literature that has a narrative story arc and does not describe true events | Includes: references to works of fiction, descriptions of plot and character Excludes: graphic novels | “I feel like that is, again, because I feel like the books are designed in fiction to make you feel good, enjoyable, that they don’t really include those children in books.” | |

| 7.2 | Nonfiction | Literature that describes true facts or events | Includes: references to works of nonfiction | “But nonfiction books are a little different. And books that have children with disabilities, most of those are describing disabilities, would be a nonfiction book. So most of those books are about information, providing information. So, if I had a student that had a brother that had Down syndrome, and if he wanted to check out a book, I think his purpose would be to get a better understanding of why his sibling is acting the way he or she is and what are some things I can do to help. So I think those books are more for information.” | |

| 7.3 | Graphic novels | Literature that tells a story through the medium of combined text, images, and speech bubbles | Includes: references to graphic novels | “That’s what I’ve been working on this past year is really, you know, looking at my graphic novel section and and trying to see you know what the characters look like. “ | |

| 8 | Portrayals | Description of disabled characters in literature | Includes: stereotypes, realism, attitudes about disabled characters Excludes: attitudes towards disabled people in real life | “The books that I’ve read about students with disabilities have been very encouraging. It’s more about the things that they can do and how they overcome those challenges that they face, things that we find hard that they’ve overcome and they found creative ways to be successful.” | |

| 8.1 | Frequency | The relative frequency of the presence of disabled character | “Recalling from all my years of being a media specialist, do not recall a lot of books where the characters have been disabled, where they’ve been either deaf, blind, or wheelchair.” | ||

| 9 | Readership | Student interest in books featuring disabled characters | Includes: reasons for reading books about disability, popular reads, student attitudes towards books with disabled characters | “I would say they’re pretty popular, like the kids like to read stuff about, like I said, things that they might them themselves be going through, or somebody that they know.” | |

| 10 | Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) | Educational focus on developing skills associated with social and emotional maturity | Includes: education about emotions and coping strategies | “We don’t use our counselors in, I feel like, the way that we could to educate our students a little bit more about empathy and them seeing each other and putting each other in their different shoes, you know. So I feel like it’s harder at the middle school level because we don’t have, like SEL curriculum or, you know, and I feel like we need it now more than ever. And we need to be able to catch these things and…And just education is just the basis of what of what we need to do to stop that type of hatred and hate speech.” | |

| 11 | COVID | A pandemic disease that caused significant disruption in schools, including a prolonged period of virtual learning | “especially last year, they weren’t allowed to walk around and browse the shelves because of COVID, so the only way that they had to search for titles to pick out and put books on hold” | ||

| 12 | Students | Description of the adolescents attending a middle school | Includes: descriptions, demographics, anecdotes, student thoughts and concerns, disabilities among students | “Because a lot of our kids are, like, struggling with stuff like that.” | |

| 12.1 | Relate to | Emotional connections with works of literature that portray an experience similar to one’s own | Includes: Kids connecting with or relating to characters | “The kids really likes, you know, books that they’re able to relate to” | |

| 12.2 | Empathy | Sensitivity towards the suffering of others | Includes: anecdotes, student consideration for and acceptance of peers | “Disabilities is one of my key things that I’m always looking for, whether we have those students or not, ’cause I feel like it for sure helps with our empathy” | |

| 12.3 | Coping | Strategies to handle life’s challenges | Excludes: strategies for teaching disabled students | “A lot of things that I’m seeing now are issues relating to mental issues that I’m seeing, that a lot of talk relating to new books that are coming out, that are teens coping with anxiety and stress” |

References:

Aho T, Alter G. “Just like me, just like you”: narrative erasure as disability normalization in children’s picture books. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies. 2018;12(3):303–319.

Barrio BL, Hsiao Y-J, Kelley JE, Cardon TA. Representation matters: integrating books with characters with autism in the classroom. Intervention in School & Clinic. 2021;56(3):172–176.

Favazza PC, Ostrosky MM, Meyer LE, Yu S, Mouzourou C. Limited representation of individuals with disabilities in early childhood classes: alarming or status quo? International Journal of Inclusive Education. 2017;21(6):650–666.

Hennink, Hutter & Bailey. (2020). Qualitative Research Methods. 2nd ed. Sage: Los Angeles.

Kersten-Parrish S. Students’ conceptions of deafness while reading El Deafo. English Journal. 2019;108(6):39–47.

Ostrosky MM, Mouzourou C, Dorsey EA, Favazza PC, Leboeuf LM. Pick a book, any book: using children’s books to support positive attitudes toward peers with disabilities. Young Exceptional Children. 2015;18(1):30–43.

Pennell, A.E., Wollak, B., & Koppenhaver, D.A. Respectful representations of disability in picture books. The Reading Teacher. 2018;71(4):411–419.

Price C, Ostrosky M, Mouzourou C. Exploring representations of characters with disabilities in library books. Early Childhood Education Journal. 2016;44(6):563–572.

Resene M. A “Curious Incident” : representations of autism in children’s detective fiction. Lion & the Unicorn. 2016;40(1):81–99.

Tondreau A, Rabinowitz L. Analyzing representations of individuals with disabilities in picture books. Reading Teacher. 2021;75(1):61–71.

Leave a Reply